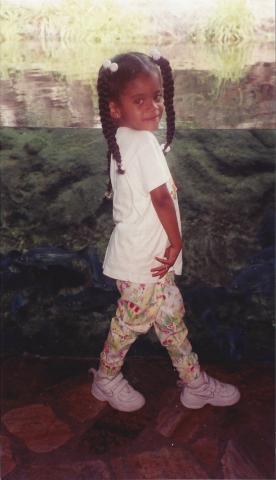

#CareFreeBlackKid

Growing up my parents answered every question, except the ones about Santa Claus and when our next trip to Toy’s R US would be, with the truth. So, when I asked them about racial inequality in second grade while doing my “Ancestry Project” for my predominately White school (P.W.I.), again my question was met with truth. My parents explained to me the impacts of slavery and Jim Crow on current practices and ideas in the United States and at seven, I understood. Later that week, I was last to present my ancestry project and as I recounted my family's’ history I could feel the energy of the room shift. Slavery was a topic my teachers wouldn’t cover until fourth grade. I believe that one of the biggest problems with the school to prison pipeline is the lack of understanding of the systematic oppression of those being impacted.

The American Civil Liberties Union describes the school-to-prison pipeline as “the policies and practices that push our nation's schoolchildren, especially our most at-risk children, out of classrooms and into the juvenile and criminal justice systems.” My parents honesty and ease at explaining the systems that I would encounter for the rest of my life were not my only tools to combat the school to prison pipeline. As children who attended public school themselves my parents made a pact that they would send their kids to private school. By making that decision, it not only meant that they would make a financial commitment to my education but they would also have more control of my school environment. Having these opportunities and parents to provide them shielded me to a certain extent from the school to prison pipeline. However, it did not blind me towards its impact on my community. Growing up in Brooklyn, NY not all my friends were as fortunate. As I grew my class privilege and my parents activeness in my education created clear distinctions between my educational experiences and those of the people around me. This not only lead me to appreciate my experiences but to work to combat a broken system. If public school in my community wasn’t a good enough option for me, than it is not a good enough option for anyone else.

The school to prison pipeline is not perpetuated by just one thing, but its failures on multiple levels to insure the just and fair treatment of youth of color. Harsh “zero- tolerance policies” have taken to criminalizing minor disciplinary issues. Today, Black youth are five times as likely to be jailed than their White peers. This is true even with reported lock up rates for kids dropping by 41% since 1995. According to new data released by the Department of Education, Black students are being introduced to the pipeline as early as Pre-K at four years old, where they are 3.6 times as likely to be suspended than their White counterparts. While “bad behavior” can often be linked to stress and trauma 1.6 million (K – 12th grade) students attended a school that employs a law enforcement officer but no counselor. This means the first line of defense in figuring out what is causing “behavior issues” and supporting children and families is non-existent. Leaving one to believe you can be criminalized before you are supported. In no way are law enforcement personnel equipped to give students the same support as a trained counselor.

Whether or not a large amount of these suspensions can be linked to a lack of cultural understanding and unavoidable bias amongst school staff is unknown, but would not be surprising. In 2011, while youth of color made up 40 percent of the school aged population, teachers of color only made up 17 percent of the teaching force. This means that 83 percent of teachers in America were White, education professors Richard Ingersoll and Henry May have argued, “minority students benefit from being taught by minority teachers, because minority teachers are likely to have ‘insider knowledge’ due to similar life experiences and cultural backgrounds.” Personally, as a student I have always found higher levels of security in classrooms with teachers of color. Not having to explain the importance of representation constantly, whether in English or in Psychology feels like one less battle in the war to receive an “A”.

There is no lack of research around racial bias and its impact in the classroom. In research published in the journal Economics of Education Review it was found that when White teachers were asked to rank the likelihood that their Black students would graduate high school they were 12 percentage points more likely than Black teachers to say they wouldn't. There has been speculation that these low expectations for Black students have to impact how White teachers interact with them. These predictions of the failure of Black youth might be provoked by the perception of Black boys as older and less innocent than White boys, a common judgment in a study done by the American Psychological Association. The behavior of youth of color is often viewed as permanent and an implication of “bad parenting, cultural deficiencies, and poor character.” While a teacher might not realize that they are being bias, these realities can not be ignored.

By focusing on these two aspects, heightened suspensions and bias among a primarily White teaching force, it is clear that students of color are at a systematic disadvantage. Understanding the system is a student's first line of defense in combating the school to prison pipeline. By understanding the system, students are able to separate themselves from stereotypes and misconceptions associated with them. The students who understands the racial history of America have a better chance at standing up for themselves or brushing off a teacher who tells them they don’t believe they can graduate or they will never amount to anything. I am a firm believer in what you believe and speak into the universe becomes your reality. If you tell a child they are bad, they are more likely to believe that they are bad and feed into that idea. As a student myself, my advice to parents will always be, to be truthful with your kids. The truth is kids make mistakes but for kids of color those mistakes are more often criminalized. Also, sometimes you don’t have to make any mistakes at all for people to judge you. Every time I go to school especially while attending a P.W.I. people in my family tell me, “Remember you’re Black.” That translates into stay aware, watch your step, and always, always be prepared to stand up for yourself or to step down after reading the situation. As an ever growing Black woman the truth has always been my first line of defense whether in protecting myself or in protecting others.

The views and opinions expressed in this post are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of MomsRising.org.

MomsRising.org strongly encourages our readers to post comments in response to blog posts. We value diversity of opinions and perspectives. Our goals for this space are to be educational, thought-provoking, and respectful. So we actively moderate comments and we reserve the right to edit or remove comments that undermine these goals. Thanks!