The Politics of Motherhood

Re-posted with author permission from the Huffington Post.

Americans, or at least the chattering class, have gotten all riled up about motherhood twice in the past few weeks.

First, there was the kerfuffle between Democratic strategist Hilary Rosen and Ann Romney about whether Mrs. Romney, a stay-at-home mother, could truly understand the plight of working Moms enough to advise her husband on the subject. Instead of turning into a real debate about the struggles of parenting and working, it turned into a question of whether the left really hates stay-at-home Moms.

Then last week, thousands of people were atwitter about how long a mother should breastfeed her child. Not only is it a completely personal decision that not has no universal answer, it also very much depends on whether a working mom can take breaks at work to pump while she is away from her baby -- a point that was decidedly missing from Time magazine's coverage.

While most people were distracted by these side shows about privileged moms who have real options to take time away from work for their children, Senator Tom Harkin of Iowa, Chairman of the Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee, convened a hearing, "Beyond Mother's Day: Helping the Middle Class Balance Work and Family," to shine a light on the problems faced by the overwhelming majority of mothers in the United States.

The fact is, working mothers, or at least those with limited education and lower-end jobs, have almost no employee benefits that allow time away from work when their children are sick or even when they give birth. Many of these moms have to work -- with more than 6 out of 10 families relying on women to bring in at least one-quarter of the family income.

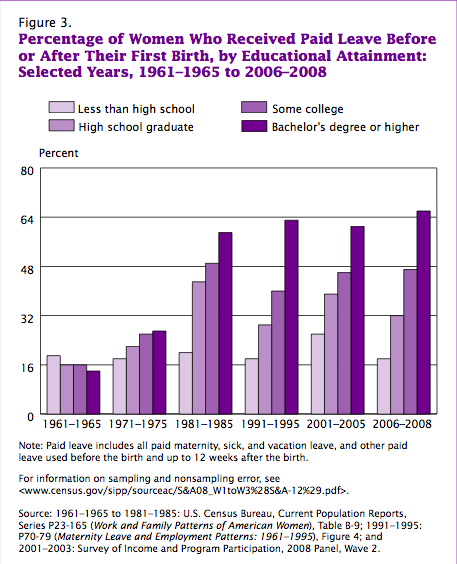

This disparity between highly-educated and economically secure mothers and those with less education and income is striking, as I testified at the hearing, pointing out that college-educated workers are far more likely to have access to paid maternity leave than workers with a high school degree or less.

The Pregnancy Discrimination Act, a federal law passed in 1978, requires employers to offer equal benefits to all workers, including pregnant women. This means that if an employer offers paid sick days or paid short-term disability benefits, the law allows women to use these benefits for pregnancy-related illnesses or for time during child birth and recovery.

The law does not, however, affirmatively require employers to allow their workers paid time off, or any time off at all, for child birth if other workers don't have the right to take time off for illnesses or injuries.

For college-educated women, the Pregnancy Discrimination Act still has made a big difference because many employers offer paid short-term disability insurance and paid sick days to attract and retain high-end employees. The law effectively requires those benefits be made available for pregnancy and child birth; thus, providing many college-educated women back-door access to paid maternity leave.

According to an analysis by the U.S. Census Bureau, from 1961 to 1965, only 14 percent of college-educated women workers received paid leave before or after the birth of their first child. The number jumped to 59 percent in the immediate period after passage of the Pregnancy Discrimination Act, and held at 66 percent in 2008.

Compare that with less-educated workers: The law has made little difference to them because they are less likely to have access to paid sick days or paid short-term disability. For workers with less than a high school degree, access to paid leave after child birth remained nearly constant from 1961 to 2008 at about 18 percent -- yes, 18 percent -- less than one for every four college-educated workers with paid maternity leave.

Congress tried to fix this disparity in 1993 when it passed the Family and Medical Leave Act, requiring employers to provide workers with 12-weeks of unpaid, job-protected leave to care for a new baby or seriously ill family member, or to recover from one's own serious illness. But only about half of all American workers qualify for this leave.

Senator Harkin and his colleagues on the committee did not have to rely on just these numbers to illustrate the inequality. They had witnesses -- Kimberly Ortiz and me.

Kimberly testified that she grew up in poverty and was determined to escape it. She went to work for a food vendor at the Statue of Liberty before having children and put in long hours, rising to Assistant Manager. But when her two boys arrived, she soon faced an unforgiving and unrelenting employer: no paid time off when her first child was born, a disciplinary write-up for taking an unpaid sick day when her son was in the emergency room, and an ever-changing schedule that made lining up child care extremely challenging.

Me: I grew up in the middle class. My parents put a second-mortgage on their home to put me through college. I took out loans and received scholarships to put myself through graduate school and law school. The end result is that today I'm a highly-educated professional worker. When my first child was born, I received 4-months of time off with full pay. When my second child was hospitalized at 6 months old, I took paid sick days to sit by his bed side. And when my children get unexpectedly ill or need to go to the doctor's, I move my schedule around -- and sometimes call my boss at the last minute to say I'm not coming in, all with knowledge that I will not be disciplined for doing so.

The real debate we should be having isn't whether breastfeeding or stay-at-home mothering is good or bad for parents and children. We should be talking about public policies that virtually ignore less-educated workers in their quest for the same family-friendly benefits provided to professional parents.

How can we expect our children to thrive if their parents are penalized when their children are ill?

Follow Ann on Twitter: https://twitter.com/Ann_OLeary

The views and opinions expressed in this post are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of MomsRising.org.

MomsRising.org strongly encourages our readers to post comments in response to blog posts. We value diversity of opinions and perspectives. Our goals for this space are to be educational, thought-provoking, and respectful. So we actively moderate comments and we reserve the right to edit or remove comments that undermine these goals. Thanks!