Behind-the-Scenes for Parents: A look inside school cafeterias to see the challenges school nutrition directors face, and how parents can help!

Eight states provide free school meals for all schoolchildren; MomsRising members in North Carolina are hoping for our state to become the ninth state to provide free breakfasts and lunches for all its students. Part of our campaign has involved holding focus groups with parents and school nutrition providers across the state. Our goal is to identify barriers to school meal access and consumption and brainstorm potential solutions. What we learned from school nutrition providers about the very real challenges they face providing meals to schoolchildren was eye-opening! As parents of children in North Carolina schools, we had no idea how many barriers school nutrition providers have to overcome to feed schoolchildren! We want to share with other parents what we learned, so you too can see how stretched thin and underfunded our school nutrition programs are.

Six school nutrition directors representing five North Carolina counties participated in our focus group; although they all live in North Carolina, many of their experiences are similar to those in other states. From the moment the meeting started, it was clear how dedicated the school nutrition directors were to their mission to feed children. They were proud of recent successes that included expanding their summer feeding programs, improving access to school breakfasts, and increasing the number of schools in their district eligible for the Community Eligibility Provision (which allows high-poverty schools to provide breakfast and lunch at no charge to all students).

It was also evident how much of an uphill battle it is to run a school nutrition program. As a parent who is grateful for the school meals my children eat at school, I was surprised to learn how underfunded, understaffed, and under-resourced these programs are. The biggest challenges they shared were the low reimbursement rates, the labor shortage and lack of staff culinary skills, and outdated kitchen equipment.

Low Reimbursement Rate per Meal

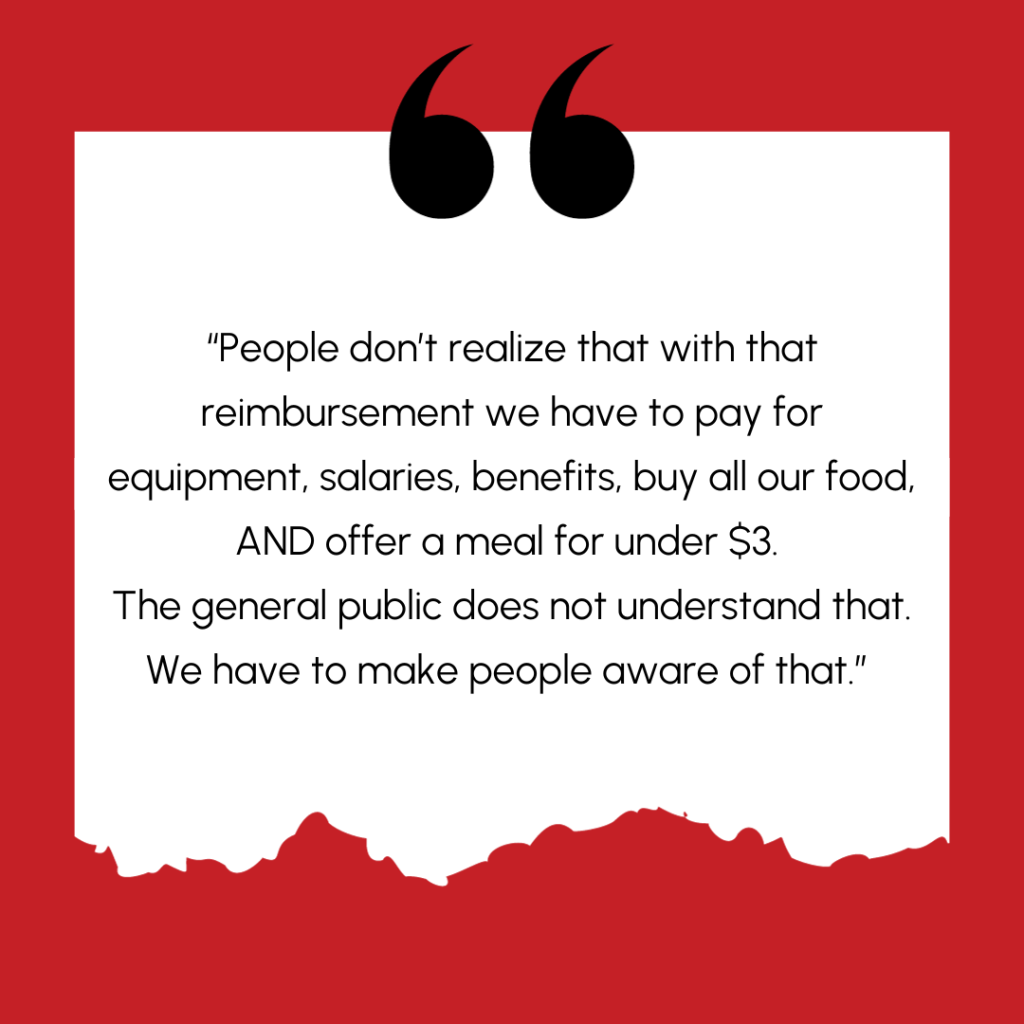

One director summed up the challenge this way: “The lower reimbursement rate is our number one problem. The rate has been reduced this school year, which means that a rate that was already low has dropped even lower. The rate is 50 cents for a paid student lunch and 38 cents for breakfast (which is free for all students in NC)– there is nothing that costs that little money. There is no incentive to feed a paid child because you lose further. You lose more money the more paid children you feed. Why are we having this burden? It doesn’t seem right.” Families are theoretically supposed to make up the difference and pay for the cost of a school meal; however, many cannot afford to do this, and school districts end up with that debt. Another director put it in these stark terms: “People don’t realize that with that reimbursement we have to pay for equipment, salaries, benefits, buy all our food, AND offer a meal for under $3. The general public does not understand that. We have to make people aware of that.” A third director echoed this frustration: “Our #1 issue is the low reimbursement rate. Combine that with increased labor and food costs, and we have a real challenge. If the reimbursement rate doesn’t jump up to cover those costs, what are we going to do? How can we mitigate substantial loss, even though historically we’ve been in a good financial situation?” Additional state funding could help close the funding gap and help school nutrition programs cover the cost of school meals.

Labor shortage & staff culinary skills

School nutrition directors talked about the challenges caused by the labor shortage. One reason for this shortage is low pay: “We cannot get people to work because what we can pay them is not enough. They can make more per hour at restaurants, even though they don’t get benefits.” Another reason is that oftentimes the school cafeteria positions are not full-time: “Our pay has matched some of the food industry pay grade, but we are often not able to offer full time work. We would prefer to hire two part time people instead of one full time person so we have more hands there and it’s not a crisis if one person can’t come in. If we hired more full time employees, we wouldn’t have as many people in the kitchen and wouldn’t have the flexibility to do the menus we want to do. If they are not full time they do not get benefits.”

A third reason caught us by surprise: “In our county you can’t be a full time employee unless you’re willing to drive a bus. That limits the number of people I can hire. There are a lot of people who work 29.75 hours per week since they don’t drive a bus.” The fact that some school districts require cafeteria employees to also drive buses creates additional problems: “We also have dual employees who work in the kitchen and also work in child care or driving buses, so that creates scheduling issues with the kitchen.”

Even if they do find staff, “they don’t have the culinary skills. They don’t understand why we have to do the things we do.” Another director adds, “ Trained labor is a big barrier. People don’t understand what they’re doing. Lack of culinary skills and the labor shortage go together. Skills that are lacking are knife skills, cashiering skills, safety training with food and equipment, swapping out old with new products, stuff like that. Even if they come from fast food, fast food is not the same because we’re doing more fresh food. There’s more technique that we have to do that they’re not knowledgeable of.”

Outdated kitchen equipment

Cafeteria equipment is expensive and often unaffordable for school nutrition programs. Here is what one director had to say about this challenge: “We have equipment that is 15+ years old, some that is 20-30 years old. Staff do take good care of the equipment but we need to modernize to be more efficient. New equipment would help staff work more productively.” Another director shares, “One of our schools needs a new hood right now. Evaporation is coming down and it’s an old hood that just can’t do the work. There are always several items that need to be updated.” The problem is systemic: “When you start in a new school district, you have money to replace or buy all the new equipment at the same time- for example, all of your walk in coolers. So eventually when they get old and break down, they all break down at the same time. You won’t have that start-up amount of money when they break down.” Some districts do their best to keep their equipment running as long as possible: “we just had to keep patching equipment, but you can only do that for so long because they don’t make parts for our equipment anymore. We do keep our old equipment as long as we can repair and replace parts though.”

Sometimes the challenges are interconnected and build on one another. In this example, inadequate kitchen equipment along with staff having to drive buses compounds the problem: “We have some very old serving lines that don’t hold temperature well or are not set up for self service or partial self service. We have been doing a lot of freezers and coolers every year. We have also been adding combis, which helps with quality cooking. We don’t have but want to get blast chillers. If we’re trying to cool leftovers down to 70 degrees within 2 hours and then have only 4 more hours to get the food down to 40 degrees, that’s very difficult because our staff have to drive buses too. So if we finish lunch at 1:30 and staff have to leave at 2:15 to drive buses, there is not enough time to cool the food down. The blast chiller would help a lot with time, since after lunch staff is busy trying to close out paperwork, cool the food down, and clean up the dining room and kitchen. But then we might have electrical problems because some of the older schools can’t carry enough power for new equipment.”

Creative Ideas

School nutrition staff find creative ways to overcome these challenges. For example, “we are focused on what we can do with the commodity foods we get. We try out different recipes. I was a chef before coming into this program, so I put a lot of effort into cooking. I hit a roadblock with the kids since a lot of them are not used to eating home cooked foods, so I have had to find a balance that we have learned over time. ” And, “We make our own spaghetti sauce. We do a mixture of prepared sauces and do final mixing and adding to them. This year we’re doing our own mac and cheese– making our own cheese sauce, cooking the noodles, adding spices and herbs to it. The ready-made mac and cheese was getting too unaffordable so that’s why we started making it ourselves.”

What is Possible

School nutrition directors ask for “reimbursement that will cover our actual costs.” They add, “The way that the system is set up just under reimbursement is not set up for meals. It comes down to us having to sell supplemental items just so we can break even. I don’t know why that hasn’t been dealt with over the years.”

Here is what these school nutrition programs are able to offer their students, and what they would like to sustain and scale up:

- “We would like to offer more fresh, local items. We do this already, but fresh, local products come at a higher cost so I would like it if we were offered incentives to use more local items. I would like to be offered an extra 10 cents reimbursement for local foods, like some states do. That would give us the incentive to offer more fresh, local foods. If we were able to offer fresh foods, sodium would naturally be reduced, so we would meet federal goals and the menu would be so much prettier!”

- “We are in the process of building up our local farm to school base. We include minimally prepared fresh local produce in our meals- this is something that we can market. The community gets on board with this, and we can build excitement with kids for the menu. I see success building over 2-3 menu cycles, when it becomes a staple. It’s a matter of kids trying the new food and telling their friends that it’s good.”

- “We have to keep trying. As a dietician, I know that it takes about 30 tries for a child to like a new food. Because reimbursement for school meals is based on participation, too often if kids don’t eat a new food the first time it is served, it is removed from the menu, but only to stay in good financial standing. So being financially stable is more important than making sure that children get good nutrition. We know that we need to operate new foods on a few cycles before kids find it acceptable to their taste buds. So what we do is incorporate a few new items into already-established foods. For example, kids like burgers, so for “Tailgate Thursdays'' we offer a local item like grass-fed beef, but it’s still a burger. And we offer toppings that are local and have no additives. This means finding a balance.”

- “Scratch cooking means you need more staff, more time and greater skill level. This translates into more training for your staff. When you have to serve 8,000 kids in 2 hours, with only 2 hours to prepare beforehand, and you have to meet so many requirements, it’s a difficult task. Especially when you are cooking in small kitchens with very little equipment. It takes skill, team effort, and directors that empower their employees to encourage them to try scratch cooking. Directors need to encourage staff to try samples and test tests to get children accustomed to new items. We need to educate employees that it takes several cycles for children to adopt new foods. But we just don’t have the time.”

The Case for School Meals for All

The Food Research & Action Center’s Report The Case for Healthy School Meals for All demonstrates how universal school meals for all students in the U.S. would go a long way to addressing the problems shared by these focus group participants. School meals for all would increase student participation in school breakfast and lunch, which would improve the finances of school nutrition programs. In addition, if free school meals were made available to all schoolchildren, school nutrition departments would be able to shift the significant amount of time and resources they now spend on the burdensome administration of school meals applications, eligibility paperwork and collecting school meals fees into serving nutritious meals. When we asked the directors to name one thing they would ask for to support their child nutrition program, they replied, “Free meals for all NC students!”

Parents, here are three ways that you can take action:

1. Share your story here about how universal free school meals would help your family.

2. Consider encouraging your child to eat school meals, if they do not do so already. Check out the school meals menu and give it a try!

3. Share this blogpost to spread awareness of the heroic efforts of school nutrition providers to feed our children. The one silver lining that emerged from the pandemic for school nutrition directors occurred during meal pick-up, when “parents got to see what we actually offer in the schools and appreciate the food that we’re serving.” Let’s continue to raise this awareness!

The views and opinions expressed in this post are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of MomsRising.org.

MomsRising.org strongly encourages our readers to post comments in response to blog posts. We value diversity of opinions and perspectives. Our goals for this space are to be educational, thought-provoking, and respectful. So we actively moderate comments and we reserve the right to edit or remove comments that undermine these goals. Thanks!