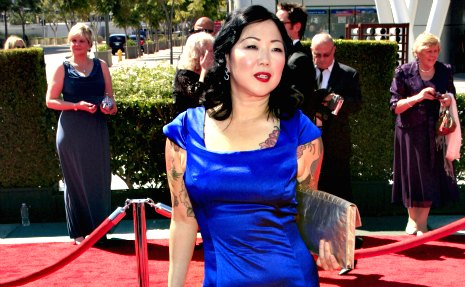

Margaret Cho in the Korean Spa: On Birthday Suits and Birth Rights

This story originally appeared in BlogHer.

Image: © Future-Image/ZUMAPRESS.com

Image: © Future-Image/ZUMAPRESS.comHaving grown up Korean-American, I know what the women's sauna is supposed to feel like: part community center and part feminine retreat. Everyone is naked, from grandmas to toddlers. There are aisles and aisles of showers, and in each one you see mothers scrubbing down their giggling daughters, or granddaughters gently washing their grandmothers' hair. Strangers make small talk, watch TV, share toiletries, and do masks or give advice to each other. It is part of the Korean female upbringing, where Korean girls grow up seeing with their own eyes what real females look and act like. There is no gawking at or judging other people's nudity, no matter the condition of one's body. Kids learn early that each scar represents sacrifice, each fold is history.

In her post, Margaret mentioned that when she was a child, her mother also brought her to the jjimjilbang, and she has memories similar to mine. She is now that child grown up, and has every cultural and practical right to be there and have her body included in the mix of normal Korean bodies. However, she was basically banished from all that by members of her own tribe. Korean society is very family-based, so much so that we call adult strangers aunt (ajumma) and uncle (ajeossi). These particular ajummas singled Margaret out for shame in what is supposed to be an accepting, communal space.

To more fully understand what happened, we have to acknowledge the chasm between the worldviews of first- and second-generation Korean-American women. One raised the other with Korean values in an American environment; somewhere along the way, we second-generation women disappointed our mothers, probably by adopting too many American values for their tastes. We adopted many facets of different cultures and counter-cultures. We wanted to start dating in high school, and even worse, date non-Koreans. We valued the worth and desires of individuals, many times above the needs of the group. We moved out of the home before marriage, we did not quit our jobs when married, and we raised our children thousands of miles away from their grandparents.

Conversely, from our second-generation point of view, the ajummas cannot seem to let go of their daily judge-fest, of scrutinizing us like second-hand furniture. We are constantly informed of all the ways we do not measure up. Now that we are adults, we wonder if this behavior actually is powered by the ajummas' own fears of not measuring up, and them either projecting their fears onto us, or merely trying to feel better about themselves by putting down others. We chafe at the one-dimensional definition of success, which I described a few years ago as: The Good Korean-American Girl who plays the piano charmingly; who is skinny and gorgeous and fashionable, yet not vain and deflects all compliments; a woman who hums Verdi while proofreading her husband’s Ph.D. thesis on nuclear physics, with a kimchi casserole is bubbling away on the stove ... all while vacuuming (and praying to Jesus).

One irony of Margaret's incident is that many of her tattoos are actually homages to her Korean heritage. Her tattoos are public representations of her inner spirit, which is in no small part Korean. To quote her post: "They are part of me, just like my scars, my fat, my eternal struggle with gravity." However, to the ajummas, her tattoos commit various Korean sins: they are loud, they demand your attention, and they visually set her apart from others -- thus disrupting the intimate, shared space they sought out when entering the jjimjilbang. (Some have pointed to the trope that Koreans associate tattoos with the mafia, but I am going to assume these ladies spent enough time in the States to recognize that Margaret wasn't really a gangster.)

This disconnect in worldviews between the generations ultimately has dark consequences: We are losing members of our community rapidly. Asian American women over 65 have the highest suicide rate in their age bracket, and younger Asian American women, between the ages of 18 to 34, have the highest rates of suicidal ideation, planning, and attempts. Although there are many complex reasons behind these statistics, in general the community is plagued with feelings of depression, isolation, and lack of support. Mutual alienation between generations cannot be helping.

Second-generation Korean women, we can take this jjimjilbang incident as a reminder to try to bridge the gap. Let's take our mothers, our aunts, our grandmothers, our elderly neighbors to the spa. Let's scrub them down like they scrubbed us, and insist that they relax and allow themselves to be pampered because they deserve it, just as we know deep inside we deserve it. Let's show the first generation that they did raise us right, that we remember how much they sacrificed to raise us in a foreign land with more material opportunity, that we do want to inherit the cultural birthright that the jjimjilbang represents. And let's also bring our daughters, so the education continues to another generation.

Let's go back to what the jjimjilbang was originally meant for: a place where women can simply be themselves and only themselves, free from the male gaze and influence, where nudity is refreshingly separated from sexuality, a place where girls learn what real bodies look like, and how we all pretty much become the same lumpy shape in the end. Let's wash ourselves, and each other, clean.

The views and opinions expressed in this post are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of MomsRising.org.

MomsRising.org strongly encourages our readers to post comments in response to blog posts. We value diversity of opinions and perspectives. Our goals for this space are to be educational, thought-provoking, and respectful. So we actively moderate comments and we reserve the right to edit or remove comments that undermine these goals. Thanks!