Courtesy of John Torous

To App or Not to App: American Psychiatric Association Issues Guidelines to Evaluate Mental Health Apps

In a landmark act of medical leadership, the American Psychiatric Association in January released guidelines to help patients and their clinicians evaluate specific apps. The American Medical Association has announced it will soon follow suit.

Over 250,000 health apps are currently available with over 10,000 devoted to mental health. These apps claim to offer emotional support, reminders to take medication, psychotherapy, and even cures for mental illness. Whereas medications and medical devices must be approved by the Food and Drug Administration, health care apps are virtually unregulated. These apps are available to anyone with a smartphone, currently 65 percent of the US population, and escalating.

When it comes to health apps, “there are more risks than meet the eye,” said John Torous, MD, Chair of the APA Workgroup on Smartphone Evaluation. For example, Torous said, an app for bipolar disorder advised drinking a shot of hard liquor as a cure for mania. Another app aimed at calculating blood alcohol levels, appears to have encouraged users to drink more, instead of less.

Although easily available, most health apps have little or no clinical basis. Furthermore, traditional approvals and regulations may be moot, given the dynamic nature of apps. In fact, the best apps are constantly updated for purposes of improvement, and as new security risks arise. An app evaluated one month, may be different, the next month.

“An app is living and dynamic. It’s hard to have a static score. This is something our field (of medicine) has never seen before,” Torous said.

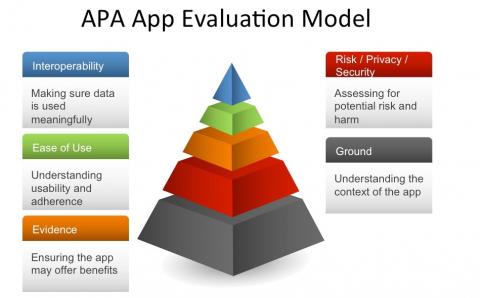

To help users and clinicians navigate this new and changeable landscape, the APA recommends “a living framework”, of evaluating apps along five criteria.

1. General Information. Understand who developed the app, and gather background information, as a context for evaluating the app. Who developed and owns the app? Does the app make claims of being medical? How is the app supported, financially?

2. Risk, Privacy and Security. Confidentiality is a core ethical principle for the medical profession. But when it comes to apps, be aware that your data might be traded or sold, and you may be profiled and tracked. The APA recommends considering the following questions: Is there a privacy policy? What data are collected? Are personal data de-identified? Can a user opt out of data collection? How is your data potentially shared?

In a study of 211 diabetes android apps, 81 percent had no privacy policy at all. Among the 19 percent with privacy policies, over half informed users that their data would indeed be collected. Only eight of the 211 diabetes apps stated that a user’s data would not be sold (Blenner, Kollmer, et. al., JAMA, March 8, 2016).

Other risks for app users include a false sense of security. Unlike a health care facility, apps cannot respond to emergencies, or example.

3. Evidence. The new APA guidelines advise that users look for research on the specific app, and reviews published by users.

Few apps have undergone clinical trials to prove efficacy, and the claims made by apps may be false. For example, the Federal Trade Commission said that the company Lumosity “preyed on consumer fears” by claiming its brain training apps could delay dementia symptoms. Thus, Lumosity possibly delayed actual medical treatment. Lumosity settled the FTC’s charges for $2-million in January, 2016.

One study identified 700 Mindfulness apps on iTunes. Many turned out to be reminders or timers. Of the 700 apps, only 23 actually provided mindfulness training or education. Among these 23 apps, there was little evidence of efficacy in actually promoting mindfulness (Mani, Kavanagh, et. al., Journal of Medical Internet Research, Aug. 19, 2015).

4. Ease of Use. How usable is the app? Does it require the internet? Does it run on iphones or android, and is it compatible with your own device? These are basic questions when choosing an app.

5. Interoperability. Apps should not fragment care. Ideally, a user should be able to easily share app information with his or her clinicians. Is data from the app downloadable or printable? Can the app share data with your electronic health record? Can it share data with other platforms (i.e., Apple HealthKit, FitBit)?

The APA App Evaluation Model was a culmination of two years of discussions and focus groups by the APA Workgroup on Smartphone Evaluation, and the Massachusetts Psychiatric Society’s Health Information Technology Committee.

According to Torous, “We’re still in the early days.” Five years ago, no studies on digital psychiatry existed in the major medical journals. Today, a scientific literature on health apps is rapidly growing.

As to whether or not apps can indeed heal—the question remains largely unanswered, and the story, like apps themselves, continues to evolve.

For more information, or for the APA’s assistance n evaluating an app, visit: https://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/mental-health-apps/app-evaluation-model

The views and opinions expressed in this post are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of MomsRising.org.

MomsRising.org strongly encourages our readers to post comments in response to blog posts. We value diversity of opinions and perspectives. Our goals for this space are to be educational, thought-provoking, and respectful. So we actively moderate comments and we reserve the right to edit or remove comments that undermine these goals. Thanks!