Last summer, Congress passed the One Big Beautiful Bill. It’s certainly big but it’s truly ugly. The centerpiece of the bill was $4.5 trillion in tax cuts that flowed to the richest Americans, offset by about $1 trillion in cuts to priority programs that allow people to build good lives, like Medicaid and Supplemental Nutrition Assistance (I’ll write more about those cuts in future posts).

But the real ugliness was in immigration. The bill’s jaw dropping price tag helped sneak the largest increase to US law enforcement spending in US history through the door: $170 billion, almost all of it dedicated to immigration enforcement and none for immigration courts or application processing.

The US is in desperate need of actual, meaningful immigration reform: a safe and orderly process that balances compassion and security. Instead we’ll get separated families, human rights abuses, fear of going to work, and horrifying images of what deportation leaves behind in communities.

I’m haunted by the recent raid on a Chicago apartment building, where children were zip tied, and some taken into custody without clothes. And by the raid at a car wash in Connecticut, where several parents were detained while their children were still in school. Officials reportedly had to determine which schools the children attended so they could be notified and ensure they didn’t return to an empty home after class. I can’t imagine what that does to a kid, or how they heal. And to think of those scared kids not only replicated at workplaces and homes across the country, but an enforcement campaign with a $170 billion war chest at their disposal, is shocking.

Immigration in the US needs resolution, not retribution.

Like most Americans, you no doubt have strong feelings and views about immigrants and immigration policy. I’m not writing this to tell you what to feel, but as an economist, I can explain what I know about immigration and, as an expert in federal policy, put that $170 billion in context.

You may be shocked to learn just how much more money the US devotes to immigration enforcement than it does for other enforcement, or even programs for children.

Table setting - Immigrants and the Economy

‘Table setting’ is one of my favorite phrases in economic circles. Before we sit down to eat, we have to set the table and get the plates, napkins, forks, knives, and such in its right place. Same with discussing a big economic issue. Before we get into it, we lay out the key facts that we know. Just like setting the table, it makes the meal that much more civilized.

So, let’s set the table on immigration in the US.

There are an estimated 48-51 million immigrants in the US today, accounting for 15% of the population.

- 24 million are US citizens

- 12 million are lawful permanent residents (green card holders)

- 2 million are lawful temporary residents (visa holders)

- 12-14 million are unauthorized

In other words, three-fourths of immigrants in the US have permission from the federal government to live here for the rest of their lives. They pay into Social Security and Medicare and earn eligibility for the program. Citizens can access public, need-based programs like Medicaid and Supplemental Nutrition Assistance (the 24 million), but lawful permanent residents (the 12 million) must wait at least five years after being awarded permanent status before they can apply for benefits. There are some very small exceptions to this, explained in more detail here or here.

Much more focus, however, is on the 12-14 million who are unauthorized. Or maybe it’s not focus, maybe there’s so much attention given to unauthorized immigrants that the permanent immigrant population gets conflated with them, despite being three times the size. Unauthorized immigrants work, pay taxes, and are ineligible for public benefits.

So why do we have so many?

Typically around 75-80% of unauthorized immigrants work–that’s about 10 million workers today–which is why the strength of the economy and the demand for workers dictates their presence in the US more than anything else.

We can look historically.

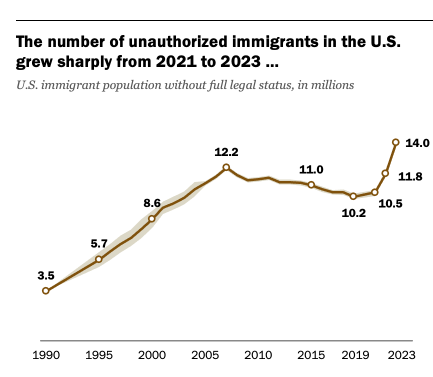

Between 1990 and 2007, the number of unauthorized immigrants increased from 3.5 million to 12.2 million. After reaching a peak in 2007, the unauthorized immigrant population fell for the next 12 years, dropping 16% in total. What happened? It wasn’t enforcement, or who was in the White House, or a wall—it was the economy. The housing bubble burst, the financial crisis took hold, and the US entered a long and painful recession followed by a slow recovery.

The number of unauthorized immigrants started to increase again in 2019 and has continued since, reaching an estimated 11.8 million in 2022. Between 2022 and 2023, the number of unauthorized immigrants increased sharply, jumping to 14 million, above what economic conditions would predict. The reason was a large jump in “protected” unauthorized immigrants.

This is confusing, because our immigration law and policy is pretty confusing, but stay with me.

The term “unauthorized,” is a residual, leftover name. If you ignore all the immigrants who have status–citizens, lawful permanent residents, visa holders, approved asylees and refugees — everyone leftover is “unauthorized.” That title has two broad classes within: individuals who are not protected from deportation and those who are. The first group is what you probably think of when you think of an unauthorized immigrant, someone who entered without inspection or overstayed their visas . They are not protected from deportation.

The second group are immigrants who were authorized to enter to the US and told to apply for status on this side of the border. They aren’t fully authorized, but they are told they won’t be eligible for deportation while their application is pending. Researchers and policymakers have always lumped the two groups together because the deportation protection can be retracted, and in fact, that is what the Trump administration is aggressively doing.

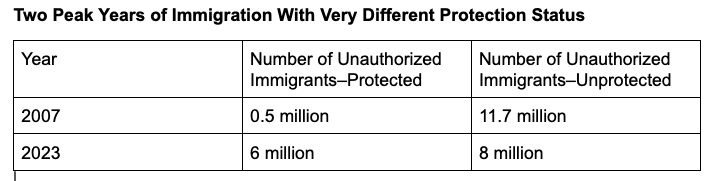

Of the 14 million unauthorized immigrants in the US, around 8 million are unprotected, a number that has been relatively steady for the past 6 years, and 6 million are protected, a number that more than doubled over the same period.

Just to give you a comparison, in 2007, the prior peak of unauthorized immigrant population when there were 12.2 million here, just a half million were protected from deportation.

In my mind, 2007 will always be the peak of unauthorized immigration because it is the peak of unauthorized and unprotected immigration.

And for what it’s worth, unauthorized and protected, aka, “did not have permission to enter the country but were let into the country with instructions of how to gain permission and therefore should be protected from deportation, in theory” is a status that wouldn’t exist in a country with a functioning immigration system.

Regardless, as an economist, there’s three things I want you to know about immigrants.

1) They make the economy bigger

The size of the economy is a direct result of the number of people in it, because such a large part of the economy is household spending. So, Texas and Wyoming could have identical economies—same industries, same age and race composition of the population—but Texas will always be bigger because it has a much higher population. It doesn’t matter if the person is an immigrant, or if that immigrant is unauthorized or not. More people equals bigger economy. That benefits everyone.

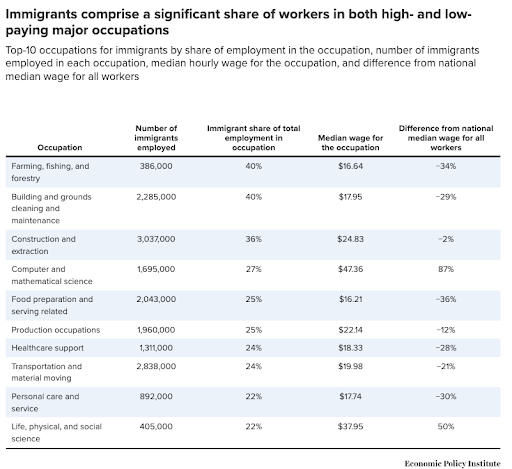

But, immigrants (authorized or not) actually have an outsize, larger-than-typical impact on the economy because they have such high work rates compared to native born. Immigrants (authorized or not) tend to be working age, while the native born population has large non-working populations like children and the elderly. By some estimates, immigrants are 14% of the population but 18% of the economy.

For what it’s worth, even the most stalwart anti-immigrant economists would not dispute that immigrants, regardless of authorization, make the economy bigger or that they work at much higher rates.

2) They don’t take our jobs or hurt native-born workers

The idea that immigrants ‘take our jobs’ assumes that there are a fixed number of jobs in the economy and immigrants (both authorized and not) are essentially the "low bidders” that get jobs because they are willing to work for less. Neither are true. Jobs reflect the size of the economy. It’s not as if New York City has more jobs than Skokie, IL because it was assigned more–it supports more through its larger economy and larger population.

It’s a wonderful positive feedback loop in our economy: as more people work, they make the economy bigger through their productivity and spending, creating a larger economy and more jobs.

And if you think that’s BS, replace “immigrants” with “women.” It was a common argument in the 1970s and 1980s that is having a small (and frankly terrifying) renaissance today: women hurt men when they start working because they take jobs from men. Economists call this the “lump of labor fallacy,” the idea that jobs in the economy are zero-sum, which is categorically wrong. If you think that immigrants take jobs, then you think women do too.

A separate argument is that immigrants (authorized or not) don’t steal jobs, but because they are paid less or are willing to be paid less, lower the wages of native-born workers. Unlike zero-sum jobs, this is possible. However, the evidence just isn’t there. The National Academies of Sciences did a comprehensive study on the effects of immigration on the US economy and found that the effect on wages were trivially small (and that immigration is a driver of long-term economic growth in the US). More recently, a set of economists did a review on wage effects of immigrants and found the same thing.

It comes down to competing pressures. The “upward pressure” from immigrants on wages comes from economic growth. Jobs pay better in a growing economy (think of how much of a raise you’d ask for if the economy was in a recession versus not). The “downward pressure” from immigrants on wages comes from competition. Jobs pays worse if 50 people are competing for them, as opposed to five. Research finds that in the real world, these effects are mostly cancelled out. Immigrants go to where work is available.

3) They are here because we need them

If the U.S. decided tomorrow that we should have no more immigrants, with or without authorization, ever again and fully close off our borders, the U.S. population would immediately decline. It’s not just that immigrants add to the economy, in some ways, they’ve been propping it up. Without a steady flow of immigrants, our population—and by extension, our economy—would be shrinking. The native-born population is disproportionately older and everyone, immigrants and native-born alike, is having fewer children. An economy can thrive through a shrinking population, but it’s a lot harder and by necessity, it requires that a lot of businesses close.

And that’s just a body count: immigrants stabilize the size of the economy. That’s to say nothing of the unique, immigrant-specific effects on the economy.

On the labor market side, immigrants fill gaps. One in four childcare workers is an immigrant, so are 70% of farmworkers, and 24% of healthcare support. Just looking at unauthorized immigrants, industries with the highest shares of unauthorized immigrants in their workforce in 2023 were construction (15%), agriculture (14%), leisure and hospitality (8%), other services (7%), and professional/business services (7%). The major occupations with the highest shares of unauthorized immigrants were farming (24%), construction (19%) and service occupations (9%).

But as far as the contribution to the economy, immigrants’ impact comes from entrepreneurship. They start a lot of businesses, in fact they are more likely to start businesses than native-born individuals, accounting for a quarter of new businesses on average. Their businesses are both small and large, adding to the economy at all levels. In fact, researchers have been quick to point out just how many of our most successful companies were started by immigrants or the children of immigrants.

Let’s eat

One thing I hear a lot when it comes to immigration is that it’s about coming “the right way,” it’s about following rules. Our last major immigration reform was in 1986. We haven’t written rules to reflect the economy this century. And what this century’s economy teaches us is that we need immigrants, we demand them in certain jobs, and we all—-native and immigrant alike—benefit from their presence, productivity, and ingenuity.

But instead of doing meaningful immigration reform, Republican leadership authorized $170 billion for immigration enforcement in the One Big Beautiful Bill.

How Much Money is $170 Billion?

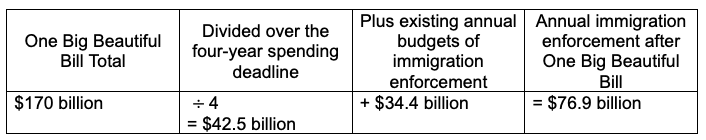

To start, it’s a confusing amount of money. Part of the money goes to enforcement agencies and increases their budget (i.e. more money for ICE), but the other part of the money goes to one-time spending (i.e. money to build detention centers). And that one-time spending has a four-year deadline, it has to be spent by 2029 or the money is lost.

So is it $170 billion this year or is it $170 billion over four years?

Let’s be conservative and say that it’s the latter, that this money will be spent evenly over the next four years. That’s $42.5 billion a year. Now add the money already going to immigration enforcement, even before the bill: $19 billion for Customs and Border Patrol, $10 billion for ICE, plus $2.2 billion of the Coast Guard’s budget and $3.2 billion of the Department of Homeland Security’s budget that is used for enforcement. That brings the total to $76.9 billion a year.

I’ve summed it up here:

Is that a lot? Y’all it’s almost beyond comparison.

Immigration Enforcement versus Other Federal Law Enforcement

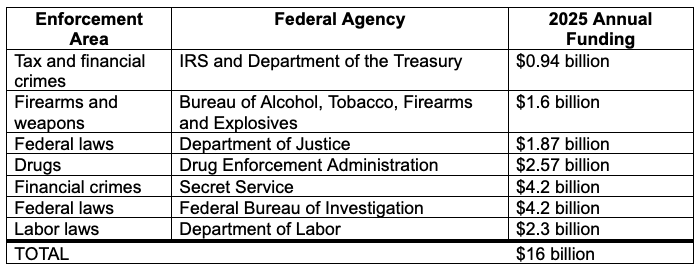

In the Table below, I show the enforcement area, the agency in charge of it, and their 2025 annual funding. Hat tip to the devoutly Libertarian Cato Institute, who put these figures together on the enforcement side, and the deeply progressive Economic Policy Institute for doing the same for labor law. Add these all together and you get $16 billion annually.

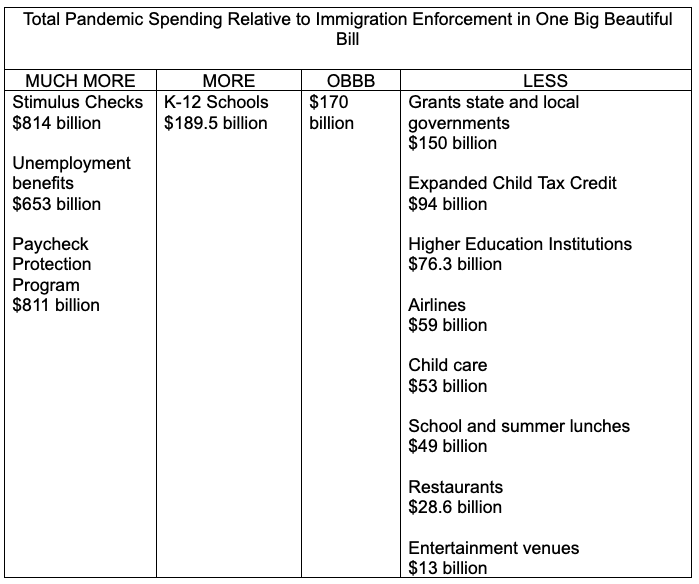

With the funds the One Big Beautiful Bill, immigration enforcement gets nearly five times the $16 billion enumerated here. In other words, the federal government devotes more than 80% of law enforcement spending to immigration and less than 20% to all other federal laws.

If you wanted to nitpick, you would point out that this is not the total federal spending on enforcement, these are just the largest agencies. The fundamental imbalance won’t change, maybe it would go from 80-20 to 79-21. The conclusion is the same: the federal government devotes a wild, incredibly lopsided amount of money to immigration enforcement.

Immigration Enforcement versus State and Local Law Enforcement

To be fair, most law enforcement happens at the state and local level and just a fraction happens at the federal level. Imagine the number of cops in your city versus FBI agents, workplace inspectors, or tax collectors.

In fact: if you were to add up spending on every police department that exists in the US, it came to about $135 billion in 2021. That’s the latest year of complete data we have, so we can assume it’s increased over the past few years. Say it’s $150 billion now. Or even $160 billion.

Immigration enforcement, at $76.9 billion, is half that. Policing 330 million people in the US and enforcing nearly all laws that are on the books gets twice as much money as policing 14 million people in violation of one.

And if you think these law enforcement numbers are wild, just wait to you see how much it compares to spending on children and families.

So How Much is $170 Billion, Really?

How large is an infusion of $170 billion to immigration enforcement? There’s two ways we can think about it: as a one-time spending infusion or in the annual terms I talked about above. Let’s do both.

So, I hate to ask but:

Remember the pandemic?

If you think of this $170 billion of immigration enforcement as a short-term, emergency spending, pandemic relief spending is a pretty fair comparison. Indeed, Congress passed legislation in 2020 and 2021 that sent trillions in relief: large transfers of money that had a limited amount of time to be spent. These infusions of money flowed to households, businesses, and states to prop up the economy and services as the country reeled from the spread of Covid-19.

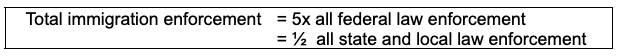

How much money did pandemic relief spend, and on what, compared to immigration enforcement this summer in the One Big Beautiful Bill?

The big ticket items during the pandemic were economic impact payments to families (aka the three stimulus checks), unemployment benefits for workers who lost their jobs, and the paycheck protection program; each were more than a half a trillion dollars in size. Smaller items include support for state and local governments, K-12 schools, higher education, school meals, to keep workers employed in airlines, restaurants, and entertainment venues, and grants to help child care businesses.

Or perhaps moms remember that in 2021, the Child Tax Credit was expanded so that all families received it, it was increased to $3,000-$3,600, and deposited directly into bank accounts for six months.

So how does it all stack up? I’ll show this first in dollar amounts:

The One Big Beautiful Bill’s infusion of money for immigration enforcement is on par with how much the government sent to K-12 schools and state and local governments in the pandemic, and dwarfs the emergency spending on the expanded Child Tax Credit, higher education, airlines, child care, school meals, restaurants, and entertain venues.

Or how about this? Developing, testing, producing, and purchasing the Covid-19 vaccine was $32 billion.

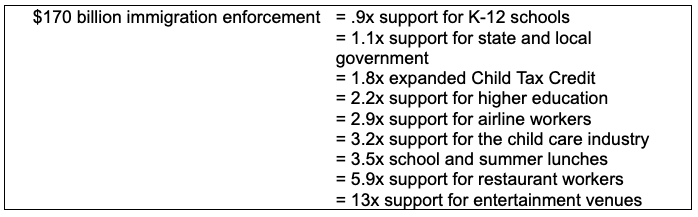

I can show it again, this time in multiples:

As a mom who truly floundered in the pandemic to try and find care and keep my job, realizing that Congress and the Trump Administration spent four times on immigration enforcement than the child care industry got in the pandemic cut really deep.

And keep in mind the pandemic was an actual emergency. The historic increase in unauthorized immigration peaked 18 years ago. The past few years have seen a spike in unauthorized immigrants the government let in with instructions to apply for status. Is that more urgent and severe than what schools (or child care or restaurants and so on) went through in the pandemic?

The Status Quo Ain’t Great Either

Rather than a one-time infusion, the other way to think of the $170 billion for immigration enforcement is to spread it out over the four-year spending window and add it to the existing immigration enforcement budget, which I showed earlier came to $76.9 billion a year.

In comparison, total spending on social programs is scant.

The federal government’s commitment to helping families afford child care is the Child Care Development Fund, which sends grants to states to distribute to families. It’s just $12.3 billion in 2025, or a sixth of the commitment to immigration enforcement.

When it comes to food, the government is more generous. It funds childhood nutrition programs (like school lunch), Supplemental Nutrition Assistance for low-income families (which used to be called Food Stamps, but the name changed when the government phased out paper stamps), and the Women Infant and Child program that buys very low-income young families formula and certain food items. But of course, all three of those items combined is less than $76.9 billion ($28.2 billion in 2024 for childhood nutrition, $40 billion for kids on SNAP, and $7.2 billion for WIC).

Arguably the most expensive thing the federal government buys for families is health insurance, and it definitely spends a lot of money on Medicaid. But here’s the thing, Medicaid isn’t a flat allotment, like everyone with Medicaid gets $15,000 a year for their health. Instead, it’s a payer based on consumption: the cost of putting a person on Medicaid depends on how much health care they actually consume. So, a 75-year-old who is an elderly care facility that Medicaid is paying for costs a lot more than say, a healthy five-year-old kid.

In fact, just 15% of total Medicaid spending goes to children, accounting for $115 billion. That’s because despite covering half of all kids in the US, kids don’t use that much health care outside of routine visits, so they don’t cost Medicaid that much.

So $115 billion to make sure 37 million kids have health insurance versus $76.9 billion to target 14 million unauthorized immigrants.

It makes you wonder what Congress prioritizes.

Kids versus Unauthorized Immigrants

The Urban Institute, a think tank in DC, puts together an analysis every year called Kids Share, where it goes through the federal budget and tax system and calculates how much goes to children. It then puts it in per person terms: how much does the federal government invest in children?

In 2023, it was around $8,990. That number was expected to fall in 2024-2027 because the last of pandemic funding was winding down to $8,440 (It could fall even more after the One Big Beautiful Bill’s cuts to Medicaid and SNAP, but some of the tax provisions will partially offset it.)

So let’s do $76.9 billion in immigration enforcement over 14 million unauthorized immigrants. That comes out to $5,492 per unauthorized immigrant.

Frankly, I don’t like how close those numbers are. About $8.5k for each child but $5.5k for each unauthorized immigrant.

What does $170 Billion Cost Us?

Sure, it’s money. $170 billion in spending costs $170 billion. I have shown here in painful detail that total immigration enforcement is more money than the federal government spends on child care or food for children, and in fact rivals the total federal investment in children. It’s worth noting that: 1) If this $170 billion went away, the money wouldn’t necessarily go to children instead. Money isn’t stopping investments in children, a lack of priority is. But also: 2) The One Big Beautiful Bill included hundreds of billions of cuts to Medicaid, health, and Supplemental Nutrition Assistance that were at least in part intended to offset the cost of the tax cuts and also this $170 billion.

Congress wasn’t doing enough for children and families before the One Big Beautiful Bill, but the Bill itself is siphoning the resources we do have to prioritize tax cuts and a harsh enforcement agenda.

That’s a tangible cost, but I’d argue there’s also a looming risk: 14 million people’s integration into society.

You’ll have probably noticed that I use “unauthorized” rather than “undocumented” throughout, and that’s because undocumented is an inaccurate term. It implies that there is a mass of people in the US that essentially live off the grid, apart from society, existing only in informal economies and off-the-book transactions. But that’s not the case. Unauthorized immigrants are enmeshed in our society with lots and lots of documents, from tax returns to mortgages.

And there’s a reason for it: up until the dramatic turn in enforcement taken up by the Trump Administration, most of our economic and social system was aligned in trying to encourage unauthorized immigrants to participate in society to the fullest extent possible.

Some of it is just a tax calculus. Unauthorized immigrants pay sales taxes for the things they buy. Even without a proper work permit, they pay into Social Security and Medicare through their automatic payroll tax contributions (they aren’t eligible or earning credits for either program) and pay income taxes through automatic withholding.

On top of this, around 5 million, or about half of the undocumented population, voluntarily pays federal income taxes through the use of ITIN aka individual tax identification numbers that are a substitute for a Social Security number for people who don’t have one. They also use ITINs to get driver’s licenses and even apply for a mortgage (yes, they pay property taxes too!)

It’s estimated that unauthorized immigrants’ total tax contribution is over $100 billion.

But a truly inestimable part of it is that the American economy—and our communities—benefit from having 14 million people on the grid, as opposed to off it. Get a job, put kids in school, call 911 when there’s a crime, go to church, get a driver’s license and car insurance, pay taxes, start businesses, grow the economy—be good, law-abiding, productive citizens in all but name. We are risking so much more than money spent, more than taxes not collected, but creating a self-fulfilling prophecy of creating the undocumented in the place of the unauthorized and losing an essential source of dynamism and productivity in our economy.

The views and opinions expressed in this post are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of MomsRising.org.

MomsRising.org strongly encourages our readers to post comments in response to blog posts. We value diversity of opinions and perspectives. Our goals for this space are to be educational, thought-provoking, and respectful. So we actively moderate comments and we reserve the right to edit or remove comments that undermine these goals. Thanks!