There could be a lot of reasons I see everything through a race lens. I have a biracial son, for instance, and I know I’m going to get questions about why a whole lot of folks who look like his mother seem to live differently than the folks who look like his father. I’m also a political scientist who focuses on race politics, so it’s my basically my job to see race everywhere.

Or maybe I see race everywhere because it really is everywhere. In the world of public policy, practically any issue you can think of can be challenged to demonstrate racial equity: education, healthcare, employment, climate change, you name it. Racial disparities are real and impact the opportunities that children of color, for instance, have compared to their white counterparts.

After having my first child last year, I started working on a book that looks at the politics of pregnancy. For the first time I thought I’d not have to apply the race lens. I’m completely consumed in the world of restrictions and regulations on women’s bodies: Can you choose whether you have a doctor or midwife? Can you try for a vaginal birth after having a cesarean section? Can you eat salami? Can you continue your anti-depressants? I thought, if anything, the world of epidurals, midwives, and soft cheese wouldn’t trigger questions about equity?

Turns out I was wrong. As I read debates, pored over legislative history, and talked to dozens of friends and acquaintances who have been pregnant themselves, my race lens has followed me. I quickly saw I couldn’t escape it because a pregnant woman’s race can play an important part of her pregnancy— different races have different access to prenatal treatment, quality hospitals, and safety, for instance.

Yes, some people concern themselves with whether they can eat deli meats during pregnancy while others worry about being victims of violence. Don’t get me wrong, I’m not ranking what I think to be valid concerns—trust me, as someone with cult-like affection for Potbelly’s, I am not judging and it most certainly was on my list of concerns. But what makes the latter group more troubling to me is that it is composed disproportionately of women of color.

Research on intimate partner violence (IPV), for instance, has shown that black women report higher rates during pregnancy (Hispanics report slightly lower rates, and enough research hasn’t been done on Asian or multiracial women). It doesn’t seem to require a study to show that violence is decidedly bad on a pregnancy, but, yes, we have research on this too: surprise, surprise, the majority of women who experience abuse experience it multiple times during pregnancy, and they are more likely not to receive prenatal care until the third trimester. There are odd details in there too, like most of the injuries occur to the head. And then race appears again—this time concerning white women, for whom the “frequency and severity of abuse and potential danger of homicide [is] appreciably worse.”

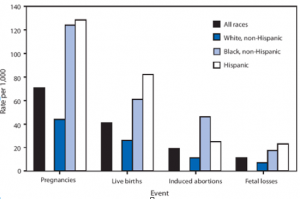

And then there were the rates of teen pregnancy that also differ by race and ethnicity. Here too, young women of color experience pregnancy at disproportionately high rates. See the chart below.

Pregnancy at such a young age influences whether new mothers will stay in school and finish the education that will eventually offer better job opportunities at higher wages in the workforce. As any parent knows, being pregnant and then raising a child will certainly make finishing school at the same time feel impossible. And so we have the dropout rates that we have—when young women get pregnant, school supports are rare (though they are wonderful when they DO exist!) and new mothers end up dropping out. And this precipitates a cascade of negative effects: without a high school diploma, women become economically insecure members of the workforce.

I fortunately did not have to worry on either of these fronts during my pregnancy. I have the good fortune to be in a supportive, healthy relationship with my partner who believes that parenting is just as much a father’s responsibility (and joy!) as it is a mother’s. I am also, woefully, one of the overeducated—the ones who prove that the education-as-it-correlates-to-income curve is, in fact, curvilinear. At some point more education (like a Ph.D.) seems to reduce wages, as many of my underemployed friends will tell you.

But, particularly on the anniversary of the March on Washington, it is important for me as I reflect on the politics of pregnancy and parenthood to think about how all mothers are not endowed equally. When Dr. King described his ideal society, presumably he meant a world where women, of any race, were enabled to lead healthy pregnancies.

When my son asks us inevitable questions about race, my husband and I are going to be honest with him and talk about race and class and the continued segregation that makes these categories determine the level of opportunities available to children. It would be great if the rest of the country could try and do the same.

The views and opinions expressed in this post are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of MomsRising.org.

MomsRising.org strongly encourages our readers to post comments in response to blog posts. We value diversity of opinions and perspectives. Our goals for this space are to be educational, thought-provoking, and respectful. So we actively moderate comments and we reserve the right to edit or remove comments that undermine these goals. Thanks!