What revolution? Why haven’t women pushed harder for caring work to be valued?

When I first got involved in blogging in the Spring of 2008 (coming up on 3 years), I started looking for other attachment parenting and feminist mothering blogs. The first feminist mothering blog that I came across and one that still holds a prominent place in my RSS reader today is blue milk. When I first discovered her blog, I found a post from 2007 called “What does a feminist mother look like” that included 10 questions for feminist mothers to think about and hopefully blog their answers to. I wrote my answers on feminist mothering here (way back in the day when no one commented on my blog). Since then, I’ve been reading and commenting on one intelligent and entertaining post after another. And now…I bring you the author of blue milk in this thought provoking guest post.

—–

Here is the feminist economist, Nancy Folbre delivering a memorial lecture on Women’s Work And The Limits of Capitalism. It’s fantastic. You should watch it. We should all be talking about it.

It’s also long (though the questions she is asked at the end by the audience aren’t brilliant so you can skip those and also, the introductions at the beginning of the clip go on a bit, so, Folbre doesn’t actually commence her lecture until the 8 minute mark of the video so you can skip the first bit of the clip, too).

All in all, don’t read any further below if you want to listen to her lecture yourself because I am summarising, quoting and paraphrasing her lecture down there and it is so much better to see Folbre deliver these arguments herself. However, if you’re going to skip the video entirely or you’ve watched it and now want to see what I am saying about it then keep right on reading.

Let’s start with where we are today. Which factor is most to blame for the modern predicament of mothers – over-worked, exhausted, stretched to capacity, idolised yet invisible, and financially vulnerable – the patriarchy or capitalism?

Folbre says she used to think that ‘patriarchy’ was the noun and ‘capitalism’ the adjective but she now thinks it is the other way around. Capitalism is to blame. She goes on to deliver a brief history of the evolution of patriarchal systems, explaining that these systems suited certain labour-intensive stages of economic development, like warfare and agricultural societies, because patriarchal systems tend to result in higher population growth than do egalitarian systems. Folbre notes that “women are often held hostage by their concern for their children”. Children have tended to weaken women’s bargaining power and historically women have often gained more reproductive advantage from marriage than men. Therefore, women have tended to also pay a higher price for it, which resulted in unequal terms in the arrangement. The patriarchal household, she explains, forced women to over-specialise in care. She then goes on to talk about how economic theories of the firm can also be used to describe what occurs in the patriarchal household. I won’t go into too much technical detail here about this, unless someone is desperate for me to do so and indicates as much in the comments on this post, but suffice to say that basically, these theories explain why the optimum outcome won’t necessarily happen through negotiation and goodwill. The reason behind this is because of the different bargaining powers of the various parties involved and the various incentives they face according to the ways in which they’re each rewarded. For instance, the owners of the firm are paid ‘the residual’ (ie. whatever is left over after all the factors of production have been paid for including labour costs) so they have an incentive to drive their labour hard and keep the residual as high as possible. At the expense of superior outcomes for the entire household, there is an incentive for men to force women to over-specialise in unpaid caring work because of women’s inferior bargaining position and access to the household’s ‘residual’.

However, capitalism has eroded elements of the patriarchy, too – although, even with their tensions the two have brought about more mutual reinforcement than significant dismantling of one another. Or as Folbre jokes, it sometimes looks like the patriarchy and capitalism are getting ready to fight each other when what we are probably seeing is the two getting ready to mate. Capitalism, which emerged with the development of wage employment has undermined some aspects of the patriarchal family. If you can imagine life just before and after capitalism: families transitioned from living and working together in their homes and generally bartering, to the beginnings of industrialisation where men left the home to earn wages working in factories, and women and children (initially) stayed behind to perform the unpaid work of managing the family home – growing food, making clothes, tending to the sick and elderly, raising children, repairing the home, collecting fuel etc. This was when caring work became truly invisible. If you weren’t paid a wage for the work in the new economy then the work no longer existed.

But capitalism, with its introduction of an ‘individual wage’ rather than the ‘family wage’ made a significant dent in the patriarchal wall – the ‘individual wage’ helped encourage women to seek self-ownership and also to engage in collective action. Now that individual efforts could be so readily identified and rewarded, women wanted to own themselves and the fruits of their own production (see here for a beautifully captured example of this). The only problem with all this revolution is that capitalism is dreadfully dependent upon the unpaid caring work of women. The breadwinner’s wage (like, the Harvester Man concept in Australia) assumed the support of unpaid work from a wife in the breadwinner’s home. It is the neo-liberal dilemma, as Folbre says, capitalism needs families but would prefer not to pay for them. However, we know that eventually women entered the workplace and became contributors to the household income, and finally that they even also challenged the notion of a breadwinner by fighting for equal pay.

As Folbre explains though, self-ownership hasn’t been enough to guarantee gender equality. This is because, among other things, women continue to specialise in producing very worthwhile things (ie. human capital, or child-rearing as us mothers like to call it) that we cannot own. Capitalism does not provide payment for services and products that are not bought and sold in markets, and who, might we ask, does most of the work that happens outside of the marketplace? Women, of course. Folbre, also briefly at this point, touches on the introduction of the welfare state, a development which saw the socialising of some of the costs of caring for dependents and which greatly enhanced the lives of women. She highlights the ways in which the welfare state has been viewed as the feminised side of the economy; how it is referred to as ‘the nanny state’, for example; and more pointedly, how it is seen as something weak, spoiling, expensive, and needing to be controlled and disciplined.

“The position of women improves but the position of mothers deteriorates – pauperization of motherhood or “motherization of poverty,” Folbre explains as the next step which occurred in the evolution of the patriarchy. Why is it that women have gained in status in comparison to men, but mothers have remained so vulnerable? In other words, why hasn’t the feminism of the last fifty years been enough? Why aren’t mothers sticking together to force change? (The economic answer would be this: capitalist competition creates incentives to exploit resources that are unpriced, especially where competitors are doing the same thing; but you may be relieved to know that we can also explain the answer with less economic terms).

Here is where Folbre’s analysis is at its most useful.

We don’t assign any value to unpaid caring work. We convince ourselves that mothering is so sacred it can’t be valued, that counting it would diminish its worth – cheapen it somehow. Folbre explains that while economists and others do in fact acknowledge that unpaid work in the home exists and isn’t counted, they also tend to assume that the consequences of this are not all that serious. This is wrong, Folbre argues. If we’re interested in material living standards, and we very much are, then we should count caring work. Why? Because it is work, because someone is providing it, and because providing this work has costs. The magnitudes of unpaid labour are really high, using the American Time Use Survey for instance, Folbre is able to show that half of all the hours of work performed in the United States are unpaid. (However, she doesn’t provide a full clarification of these hours in her lecture so I wasn’t able to determine their exact structure – do they include unpaid overtime by wage-earners as well, general work in the house, caring for the elderly, caring for people with disabilities in the home?) This means that half of the work done in the economy does not happen in the capitalist system. Folbre rightly notes that this unexamined work has really important implications for living standards.

Then Folbre throws the following puzzle to the audience.

Say there are two families, both with two parents and two pre-school aged children, and both with a household income of $50,000.

Family A – is comprised of one wage earner working full-time earning $50,000 and one full-time home-maker.

Family B – is comprised of two parents working full-time, both earning $25,000 each.

Which family is better off?

Current measures of inequality treat both families exactly the same – but Family B is in fact worse off because they are obviously having to also purchase services which are otherwise being performed for free by a full-time homemaker in the other family. Namely, childcare. It is important, Folbre points out, to put some value on that unpaid work if you want to understand the relative living standards of different households.

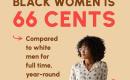

When we look at women’s equality we are mostly concerned with our market income. With women entering paid employment, household incomes have risen. And market income has become more equally distributed across the sexes. But this is because we are comparing a time when women earned zero value in market income to a time in the present where they have been increasingly earning a market income for paid employment. What happens, Folbre asks, if you assign a value for non-market work and you ask not what happened when women started working but what happened when they changed the type of work they did from unpaid to paid work?

In general, women’s unpaid work has been pretty much of a similar value across women. (There were some big shifts when the world began to understand how human capital, and thus economic growth, could be increased by the education of children – mothers were consequently encouraged to be more specialised in their mothering. Mothering capabilities have been tied to education levels, too, but generally, a mother is a mother regardless of class, education and income).

While all of women’s unpaid work has been of a similar value, women’s paid work has not been. Some women are highly paid and highly educated (thanks to feminism) and others are not, and what we’ve seen in economies like America, is that overall living standards have become much more unequal now that more women are in paid work. In a way, the patriarchy was equalising. Every married man used to get an unpaid house-keeper and child-carer – and the services provided to him were roughly of the same value regardless of the income of the man. Why is there more race and class inequality among women now? In part, it is the success of feminism in a capitalist system. Women overall have gained more education, but a lot among us have not had access to these opportunities. Poor women have been trapped in disadvantage.

Now, back to the question of this post, which is why haven’t women pushed harder for caring work to be valued? If we know that unpaid caring work – child-rearing, elder care, care of family members with disabilities – is stretching most mothers/carers to their limits why aren’t we changing things? Why can’t we get political change happening for mothers/carers? Folbre makes the rather devastating case, and I think she is right, that it is income inequality which has undermined efforts to seek change. “Higher paid women benefit from their ability to hire low-wage women to provide child care and elder care in the market”. Even if we don’t benefit directly we can still afford to ignore the plight of others. It is one of the reasons why the campaign for paid maternity leave was so slow to get going in Australia. A lot of women like myself, with education and good pay had already secured some form of paid maternity leave from our employers long before a national scheme was in place. It was women with lower incomes and less secure jobs who were least likely to have beem able to negotiate paid maternity leave in their jobs. (By the way, we finally got a Labor government who did in fact introduce a paid maternity leave scheme here).

Not only are there inequalities in financial capital but there have also been inequalities in human capital – that is, the educational opportunities of our children are not spread evenly. Increased fear and anxiety about the welfare of our children, and the competitiveness that goes with this discourages the co-operation between mothers that is needed to agitate on a political level for change. Or as Folbre explains, it is difficult to unify women around a systematic political agenda when countries like the United States of America are so fractured along lines of race and class and family structure. Increased inequality among women has contributed to a fear of collective action – in fact, the very idea of being associated with caring work is seen as unpalatable in the modern political economy. A lot has been invested in the myth of self-reliance. Caring for someone makes them dependent and being dependent undermines their self-reliance, a state of being seen as entirely repulsive in our economy and which we would prefer was privately and quietly dealt with by families in their homes on their own.

Inequality matters for political change – it affects decisions about pooling risk, redistributing income, and banding together – all parts of the solution to the problem of unpaid caring work. And inequality hurts the bottom of the income distribution the most, where it has huge legacy effects lasting generation after generation. Inequality breeds more inequality. Folbre contends that it is increased inequality among women which has led to the success of conservative movements like The Tea Party, where the political visibility of women has been striking. It is also interesting to note that this movement has been very much targeted at the welfare state – it is anti-state and individualistic. Take care of your own family first and don’t worry about how other families are managing.

So, how do we begin to change all this? Well, as Folbre argues, nothing will change until we can rally a larger coalition and to do this we need to first document and explain inequality better, and to do that? – we need to start counting unpaid caring work!

“We need a more sustainable organisation of production and social reproduction” – Nancy Folbre, want more? Try her posts on The New York Times. And of course, you can buy her books.

This writer is an economist who writes about motherhood from a feminist perspective, she is the author of the blog, blue milk. She has presented at conferences on motherhood, work and family, feminism, and social media; has written for magazines and newspapers, and has had her work quoted on television. She is a contributing author to the soon-to-be-released book,The 21st Century Motherhood Movement: Activist Mothers Speak Out On Why We Need To Change the World And How To Do It. She is also the mother of two children. She might sound like she has it together, but she so very much doesn’t. You can follow her on twitter @bluemilk.

Cross posted from PhD in Parenting

This blog is part of the #HERvotes blog carnival

The views and opinions expressed in this post are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of MomsRising.org.

MomsRising.org strongly encourages our readers to post comments in response to blog posts. We value diversity of opinions and perspectives. Our goals for this space are to be educational, thought-provoking, and respectful. So we actively moderate comments and we reserve the right to edit or remove comments that undermine these goals. Thanks!